Creating a Culture

Conservation, NewsCatalina Island Conservancy’s newly assembled Plant Tissue Culture Lab is providing the tools and technology to help save the rarest tree in North America.

Kevin Alison, Rare Plant Ecologist, Catalina Island Conservancy

Though Catalina Island Conservancy’s rare plant lab is sterile, it is teeming with life and excitement. It is here that Conservancy Rare Plant Ecologist Kevin Alison helps nature find a way to persist, developing a method to overcome the challenges of traditional propagation. Focusing on micropropagation, Alison hopes to buttress and, someday, perhaps expand, the population of the Catalina Island mountain mahogany (Cercocarpus traskiae) – the rarest tree in North America.

“We want to incorporate this advanced method of propagation into our strategy for rare plant management as it can overcome a lot of challenges we have with traditional means – especially in the case of Cercocarpus traskiae,” said Alison. “Since there are only six individual trees left, this clonal technique is critical to capture and conserve all the genetics remaining of this imperiled species.”

Through micropropagation, scientists can circumvent environmental difficulties, the species’ propensity to hybridize, and create new clones without significantly harming the existing individuals.

“Extensive hybridization with a more common relative has made collecting seed an invalid method for preserving this endangered species. Traditional cuttings are also known for having a high likelihood of failing and puts significant stress on the plants.”

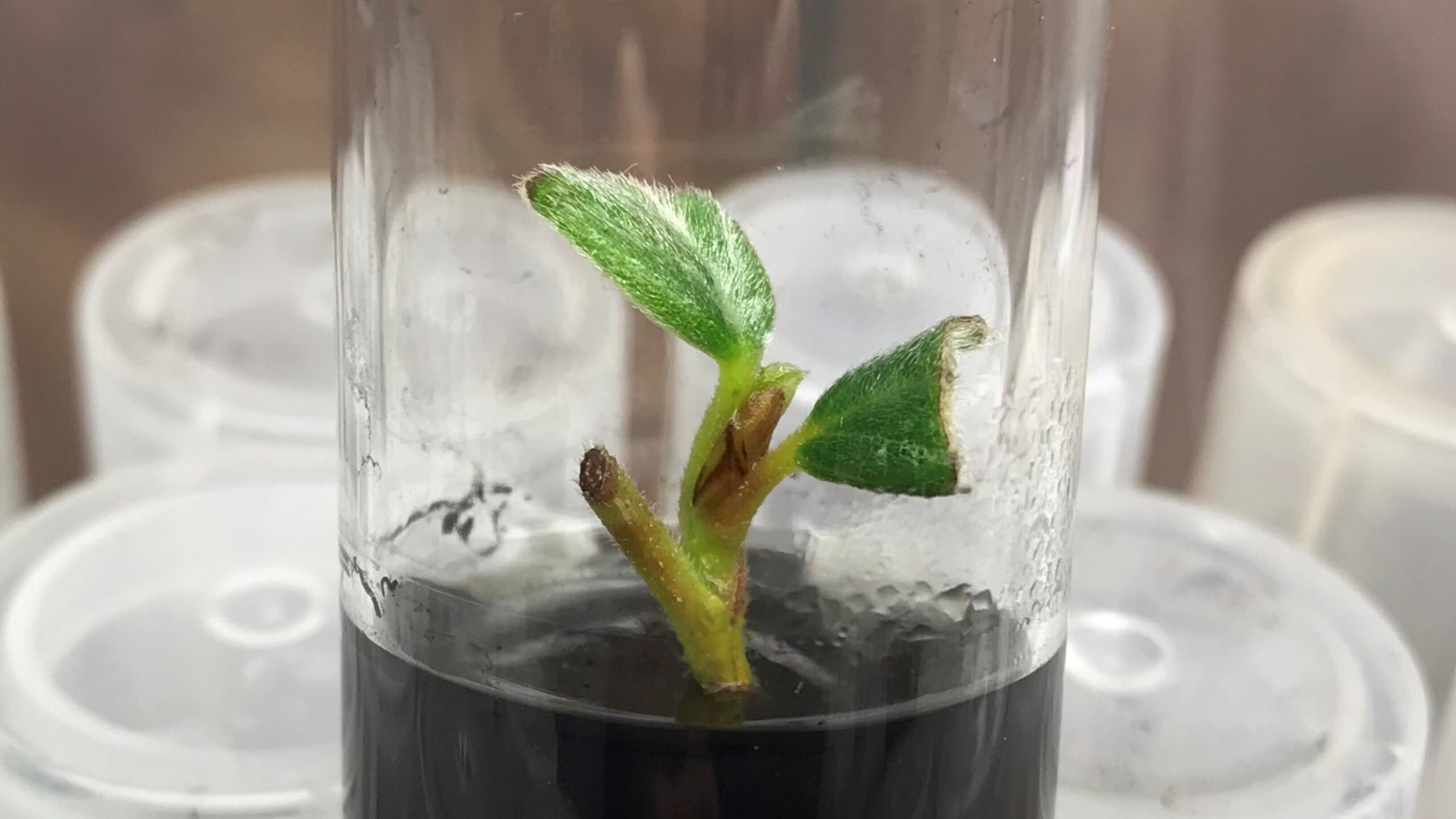

For traditional means, ecologists take cuttings that could be 4-6 inches long, putting significant pressure on the original plant each restoration effort. Instead, the Conservancy is focusing on micropropagation in which explants, very small parts of a plant used to start cultures, are prepared with precision. In-vitro, Latin for “in-glass,” propagation requires a sterile environment. Alison has been developing a protocol to chemically clean and prepare the explants – a delicate balance. The solution needs to be strong enough to remove competing microbes without harming the tiny nodes of potential new growth. Once the explants are cleaned, they are able to be cultured and put onto growing media with everything they need to thrive.

“It’s basically like a native plant nursery – but in test tubes,” explains Alison.

“This method alleviates the limiting factors of more common propagation practices make it possible for extremely rare and difficult-to-grow plants to prosper.”

Once a plant is solidly established in-vitro, it can grow and provide an avenue for rapid exponential cloning. For instance, if one plant could generate 10 plants, and those could spawn another generation, and so on and so forth until – theoretically – a million plants sprout up within six replications. A root hormone could prepare plants to be established outside where they would then be introduced to progressively more difficult environments before transplanting onto the landscape.

Currently, Alison is establishing protocols to establish cleaned Cercocarpus traskiae explants in-vitro. It is a process that involves research, experimentation, and a bit of good fortune. It is a precise pursuit, all with the purpose of protecting the rarest tree in North America from extinction.

“Tissue cultures allow us to grow a large amount of high-quality plants. Every clone we’re able to create is a greater chance to protect this tree,” Alison said. “If we have 100 individual clones of each individual tree, our chances of this species not going extinct has increased 100-fold.”