Before dusk, a group of researchers traveled to Catalina Island’s Cottonwood Dam, one of several points across the Island where they planned to conduct a bat survey. In this particular location, a shallow pool of water dotted with tadpoles seemed a likely draw for bats, which drink the water and eat insects hovering overhead. The small pool was the end point of a long corridor that bats would presumably fly through, and this airspace is where the researchers decided to assemble their traps.

“We’re going to be able to attach three mist nets, stacked on top of each other to make a tall mist net,” said LSA Associates Inc. Senior Researcher Jill Carpenter. “The pully system allows us to raise and lower the nets so we can reach – like if the bat were to fly to the very tip top of this thing, we could only get to it with this pully system.”

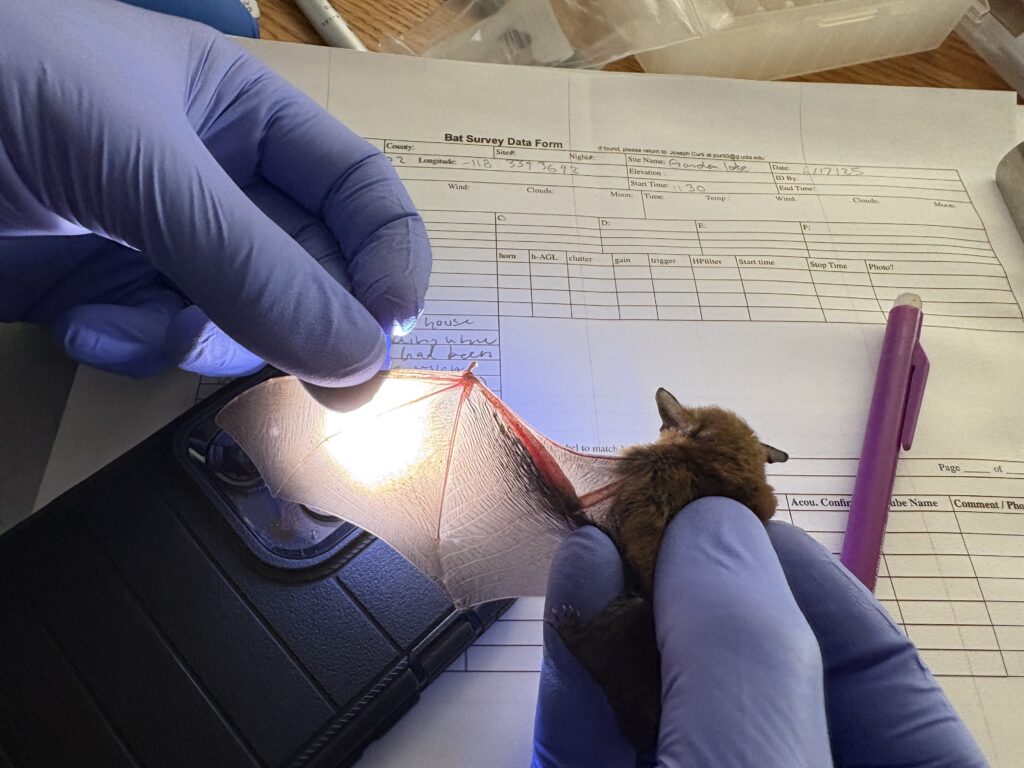

The nets, about 20 feet wide by 30 feet high, are designed to snare the small bats as they fly toward the water. Once one enters the trap, the nets are lowered to extract the bat. Wearing protective gloves and a face mask, the researchers use an instrument to collect tissue samples.

The reason for this bat survey is that a species of bat living on the Island appeared to have unusual DNA the last time Joey Curti, a post-doctoral fellow at UCLA, studied the winged creature. On this recent visit to the Island, Curti and Carpenter joined Catalina Island Conservancy biologists to collect new samples that may provide a more robust understanding of the Yuma Myotis (Myotis yumanensis).

“We take a small 3-millimeter biopsy punch from its wing tissue and from this, we’re able to extract DNA. We send it to a sequencing facility and they’re able to sequence the entire genome of the organism,” said Curti. “This small punch of skin we take from their wing doesn’t impact their ability to fly at all and heals remarkably fast, in about 12 or so days.”

In addition to the DNA extracted from the bats sampled during this field survey, Curti and Carpenter are also trying to extract DNA from three old bat specimens. Two dried specimens are from the 1970s held at the Los Angeles Natural History Museum. One other is stored in ethanol from 1893 and kept at the UC Berkeley Museum of Vertebrate Zoology. This will provide a comparison for measuring inbreeding in these populations from their first recordings on the Island to present day.

There are 10 bat species that occur on the Island either as residents or as temporary visitors. Three of these species are considered “Species of Special Concern” by the state of California and are declining on the mainland. The collection of DNA samples from Catalina bats will help provide researchers with a look at the bats’ genes to see if inbreeding is occurring within the population.

“We did some previous work on the Island and discovered some elevated levels of inbreeding in the bats here, so we’re interested in seeing how widespread that is in different regions of the Island,” said Curti.

Bats are an important element of the broader ecosystem, as they act to control pests and distribute seeds. But the potential for inbreeding could spell trouble for the health of bats, which may experience congenital deformities or irregularities that impact their reproductive development and lead to long-term population declines.

While this kind of research has been done on other island creatures like the fox in years past, few studies have analyzed wild bats in this way. So this research could offer an important look at whole genome data to provide a more accurate understanding of their genetics. Catalina Island Conservancy Wildlife Conservation Manager Katie Elder said the collaboration on the bat survey between Conservancy biologists and specialty biologists like Curti and Carpenter has widespread benefits.

“It is absolutely critical for us to have these relationships,” said Elder. “We’re a very small team – three of us full time biologists – and we’re not experts in everything. We have our strengths, but there are people who are so dedicated and knowledgeable in specific species and search methodologies, so having partnerships with them, making sure we’re doing the most meaningful, most humane, most well thought out research possible.”

This research conducted through the bat survey will help conservationists better understand the species, its evolution and interaction with the Catalina Island native environment. Learn more about the Conservancy’s bat monitoring.