Cliff Notes

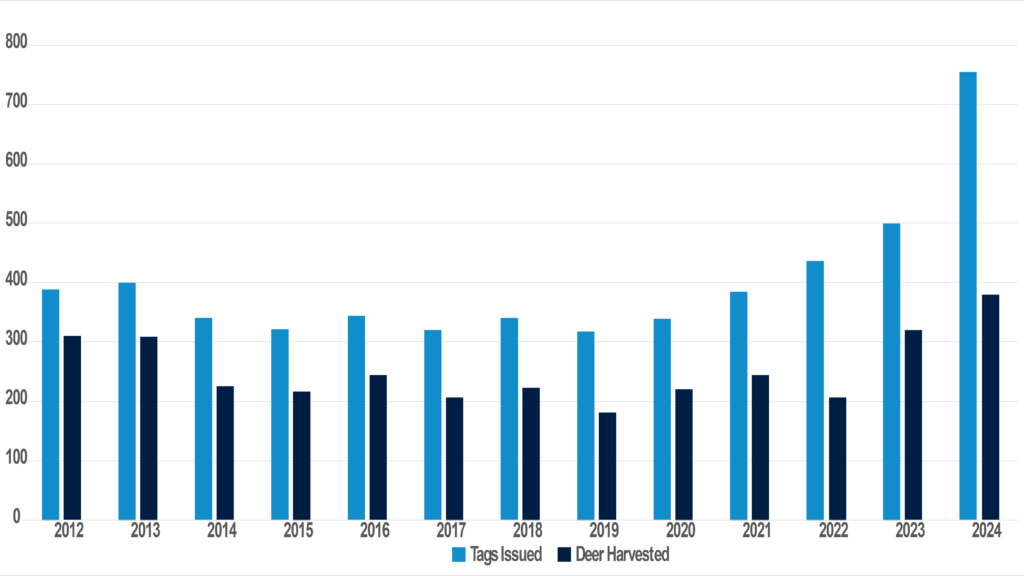

- The 2024 hunting season ended Dec. 26; yielding only 379 non-native mule deer harvested by hunters out of 754 issued tags.

- Ongoing deer browsing is fueling wildfire risks by crowding out native plants and allowing flammable invasive grasses to spread.

- Recreational hunting triggers compensatory mortality, where deer produce more offspring and improve fawn survival, replacing harvested deer with a similarly sized generation.

The 2024 deer hunting season on Catalina Island ended on Dec. 26 with hunters harvesting 379 non-native mule deer from 754 issued tags. The estimated deer population for 2024 stood at 1,800. Scientists and conservationists have raised concerns about the limited success of hunting as the primary strategy to control the deer population and protect the island’s fragile ecosystem.

Mule deer, introduced to the island in the 1930s as a game species, have become an ecological problem, significantly altering native plant and animal habitats. Without natural predators, the deer have been able to outpace conservation efforts on the island where their migration is not possible. Research shows that the deer’s impact on the habitat has allowed invasive and non-native grasses to spread, affecting native plants and animals and creating significant wildfire fuel.

Deer Impact on Catalina’s Ecosystem

For millions of years, native plants evolved without the need to protect themselves through physical defenses. The introduction of mule deer created a buffet for the herbivores, which preferred to browse on native plants and shrubs.

A 2012 study on Catalina Island found that deer browsing on native plants and shrubs after wildfire showed an eight-fold increase in plant death as compared to areas with protective fencing. In plots protected by fencing, only 11% of resprouts died. In deer-exposed plots, the die-off rose sharply to 88%. The mule deer’s preference for native shrubs and seedlings directly impacts the preferred habitat and food sources of key native species including the Santa Catalina Island ground squirrel, Santa Catalina Island shrew, Catalina California quail and the island’s ambassador —the Catalina Island fox.

Growing Wildfire Risks

Wildfire risks on Catalina Island have grown more severe due to a combination of climate change, habitat loss and invasive species like mule deer. By feeding on native shrubs, deer create space for highly flammable invasive grasses to grow—known as “one-hour fuels”—that dry out and burn quickly. These grasses now cover over 35% of the island, making it more vulnerable to catastrophic fires.

The severity of these challenges was highlighted by the 2007 Island Fire, which burned nearly 5,000 acres (10% of the island) and remains a stark reminder of the dangers. Since then, tree cover in the affected area has declined from 51.8% in 1998 to 43.5% in 2022, further increasing fire vulnerability.

By restoring native vegetation and removing invasive species, the Catalina Island Conservancy aims to reestablish natural firebreaks and reduce wildfire risks, ensuring the island’s safety and ecological health.

Hunting Falls Short

The limitations of hunting as a component of deer population control are evident. This year, 379 deer were harvested during the hunting season, a relatively steady figure compared to past years. The largest deer harvest was last seen in 2007, with 402 taken by hunters.

Additionally, increased hunting pressure triggers a biological response called compensatory mortality, where deer populations produce more offspring and improve fawn survival rates in hunted populations. This process replaces the deer harvested by hunters with a new, similarly sized generation.

“The hunting program has been a recreational opportunity for some, but it clearly isn’t enough,” said Lauren Dennhardt, senior director of conservation for the Catalina Island Conservancy. “With 42 years of data on recreational hunting, we need a different approach to restore balance to the Island’s ecosystem.”

The logistical challenges of hunting on the island are compounded by the steep terrain, management of the meat and transportation to and from the island, primarily by ferry and boat.

Each year, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife issues deer hunting tags through the Private Lands Management program. The Conservancy purchases these tags and then distributes them to hunters at cost. However, despite an increase in tag purchases, the deer harvest has not risen proportionally.

DEER HARVEST NUMBERS

Advancing Research on Island Deer Behavior

The Catalina Island Conservancy has launched an initiative to study deer movement and how factors like seasonal hunting pressure and drought affect their behavior. As part of the project, 16 deer were outfitted with GPS-enabled collars in September 2024 to track their movements. One deer was accidentally harvested during hunting season, and another died of natural causes. The collars are designed to fall off naturally after about a year, allowing researchers to collect and analyze the data.

This research aims to identify new fire-prone locations where deer are spending more time browsing on native plants, allowing non-native, flammable grasses to take over. The collected data will be shared with university partners to contribute to broader scientific understanding of general deer behavior and their contributions to the damage to habitats.

The Path Forward

The failure of the 2024 hunting season underscores the urgency of moving forward on the Catalina Island Restoration Project, which hinges on the removal of all invasive mule deer from the Island.

For more than 50 years, the Catalina Island Conservancy has worked to protect the Island’s unique biodiversity by managing 88% of the Island’s 48,000 acres. The Catalina Island Restoration Project focuses on habitat restoration, plant regeneration and species management. These efforts are critical for preserving more than 60 plant and animal species found nowhere else on earth, including the Catalina Island fox and North America’s rarest tree, the Catalina Island mountain mahogany.

Island restoration on neighboring Channel Islands has achieved amazing success. For example, on San Clemente Island, conservation efforts led to the removal of goats by 1991 and pigs and deer in the 1990s. These efforts resulted in the recovery of five species—four plants and one bird—which were delisted from the endangered species list in 2023.

“Catalina’s restoration requires bold action,” said Catalina Island Conservancy President and CEO Whitney Latorre. “The removal of invasive species from nearby islands like Santa Cruz, and islands around the world, demonstrates how ecosystems can recover and thrive. It’s time to apply those lessons here.”